The Origins of Syphilis: Why Narratives Matter

The first recognized syphilis outbreak in Europe dates from around 1495. Then known as the Great Pox, it spread from Italy to France and across the continent. It was referred to by various names (the Neopolitan disease, the French disease), each label hinting at a perceived point of origin and placing blame. Many believe the illness originated in the Americas and, via Columbus’s crew, spread through Europe after the French invasion of Naples, when the soldiers returned home.

The Naples campaign itself was a chaotic affair, drawing together mercenaries from across Europe, soldiers moving from battlefield to battlefield, and women who followed armies for trade, sex, or survival. In such conditions, infections of all kinds (plague, dysentery, influenza) were rampant. The Great Pox entered this volatile mix and spread with terrifying speed. Accounts from the time describe soldiers with grotesque sores and disfiguring lesions, leaving little doubt that this was something new in its ferocity.

During the COVID-19 outbreak, we were reminded of how naming a disease after its supposed place of origin or the people believed to be transmitting it can stigmatize groups, cultures, and communities . But geography-based prejudice is not the only harm: disease narratives can reinforce older, more insidious biases as well.

Syphilis: Woodcut, 1496. Wellcome Collection.

The timing of the 1495 outbreak coincided so neatly with Columbus’s return from the Americas that it seemed to confirm the so-called Columbian hypothesis: syphilis was imported into Europe by the crew of the voyage. This perspective assumes that Europe was free of syphilis until some rowdy sailors brought it back from the “New World.” The implications are significant—this framing casts Indigenous peoples as the original source of Europe’s suffering (Farhi and Dupin 2010; Louis and Louis 2025).

An alternative is the Pre-Columbian hypothesis, which argues that treponemal disease (illnesses caused by Treponema pallidum, which has a subspecies, Treponema pallidum pallidum, which causes syphilis) was already present in Europe long before Columbus, but was either rare or unrecognized until the Naples outbreak of 1495. Skeletal remains with treponemal lesions have been found in medieval Europe, though diagnosis is often difficult to confirm.

Some historians and scientists have since suggested a third path: the so-called combination theory (Crosby). This idea proposes that treponemal diseases already existed on both sides of the Atlantic in non-venereal forms, such as yaws or bejel. The Columbian voyages and the violent social upheavals that followed may then have provided the circumstances in which these bacteria adapted into a more aggressive, sexually transmitted form. This would explain why skeletal evidence of treponematoses appears in both Europe and the Americas before Columbus, and why genetic studies today find multiple deep lineages of T. pallidum.

Such a perspective emphasizes that disease is never just a matter of biology; it is also about ecology and society. Whether a treponemal infection manifests as a childhood skin disease in the tropics or as a devastating STI (sexually transmitted infection) in Europe depends as much on living conditions, poverty, and climate as it does on the microbe itself.

Every so often, as new discoveries come to light, scientists make headlines and misinterpretations of original research follow. This can contribute to the reinforcement of prejudices. Even The Guardian, a reputable publication, slips sometimes. In December 2024, an article appeared in the newspaper entitled “Ancient bones shed new light on debate over origins of syphilis,” suggesting that:

“Now, ancient DNA recovered from skeletons across the Americas has shed light on the mystery. The disease-ravaged bones, which predate Columbus’s first voyage to the New World, harboured genomes of bacteria from the syphilis disease family, suggesting the infection had its roots in the Americas”

Even though the researchers responsible for this were much more cautious, the reporter gives the appearance of a firm conclusion. In reality, the Max Planck Institute team showed that the bacterium, T. pallidum, was present in the Americas 9000 years ago. They suggest that from there it went to infect Europe and that, because of colonial and political influences, it continued its expansion from there. T. pallidum has several subspecies, but only one of them is the cause of the sexually transmitted infection we know as syphilis. The findings of the Max Planck team relate to T. pallidum but have not shown conclusively that the sexually transmitted infection (that is, T. pallidum pallidum) was present in the Americas. Still, their research has the potential of being used to continue to uphold a colonial narrative that thrives on the oppression of Indigenous peoples.

Another team, however, demonstrated that T. pallidum was present in bones from around 650 CE uncovered in Roquevaire, France. This, together with phylogenetic analysis demonstrating the wide variety of T. pallidum in Europe, suggests that it would not be amiss to imagine a much more complex evolutionary history of the bacterium, which might have been present in two separate lineages.

To insist on an exclusively American origin of syphilis is not a neutral scientific claim. In the sixteenth century, it was mobilized to portray Indigenous peoples as sexually immoral, unclean, and dangerous. By contrast, Europeans were cast as the hapless victims of a foreign scourge. This framing ignored the realities of conquest, enslavement, and sexual violence that created new pathways for disease transmission. It is not difficult to see the continuity with later prejudices: the stigmatization of Haitians during the early HIV/AIDS epidemic, or the scapegoating of migrants in contemporary tuberculosis outbreaks. In each case, disease origins become a convenient excuse for reinforcing social hierarchies.

It is disingenuous to deny the implications of insisting on an American origin for syphilis without acknowledging that even if such were ultimately to be irrefutably shown, it would likely serve narratives of oppression and reinforce negative stereotypes we are fighting to put an end to. Diseases are not the exclusive domain of a particular group of people and should never be treated as such. Instead, we would do well in asking ourselves who benefits from the Columbian origin narrative, a narrative that doesn’t necessarily acknowledge the colonial powers' role in the spread of syphilis, independently of whether the strain came from the Americas (where Columbus’s crew were unlikely to have engaged in consensual sex with Indigenous people), Europe, or Africa (where it might have been propelled by the slave trade).

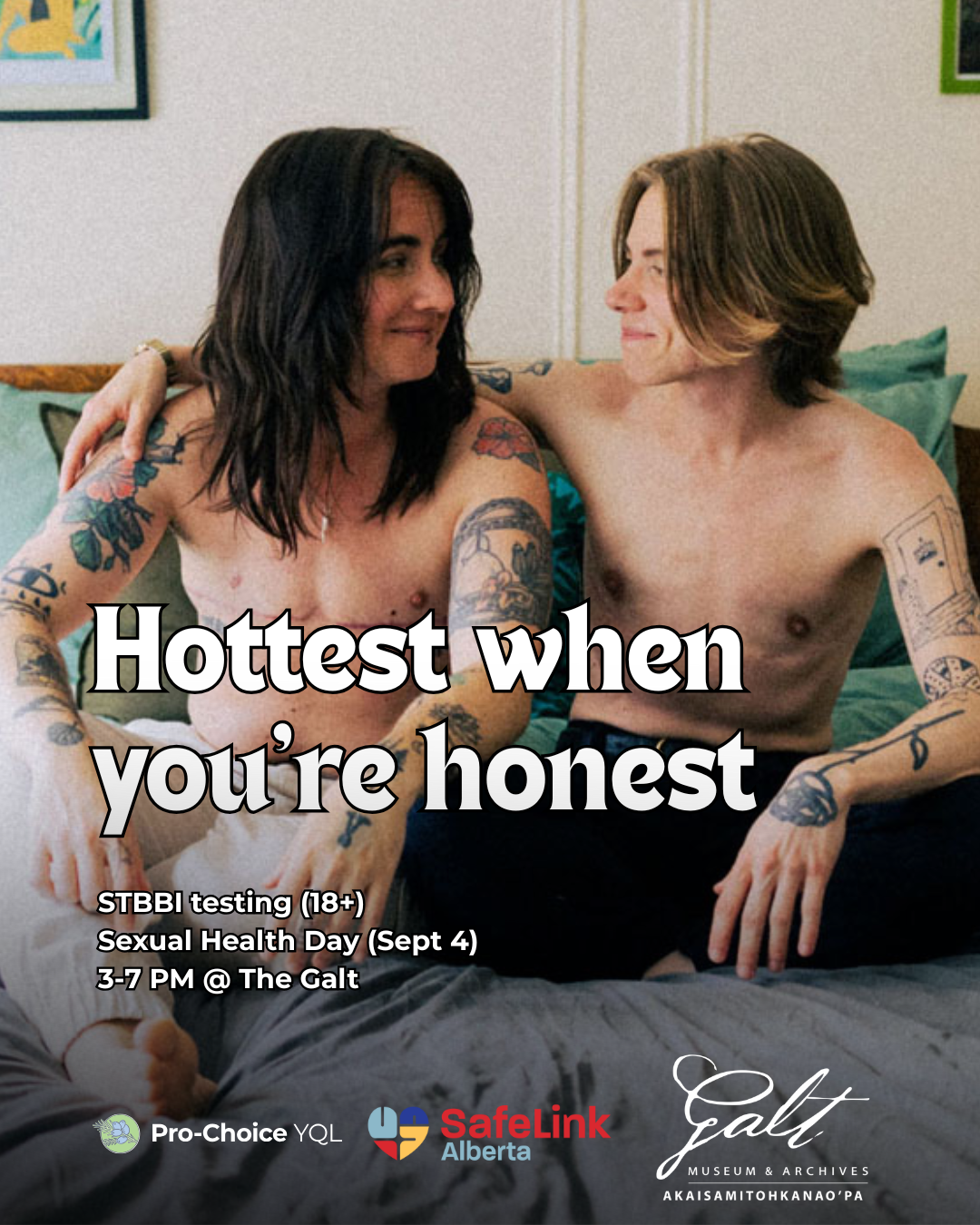

Part of our fight against stigma today is to demystify syphilis—and other STIBBIs (sexually transmitted and blood borne infections)—and to break the silence around them. The history of syphilis shows us that diseases are never just biological—they are also social and political. Recognizing this is part of building healthier, more just futures.

From the “Great Pox” of 1495 to modern STBBI stigma, origin myths have been used to scapegoat communities while ignoring the social and political forces that drive outbreaks.